Reference

GopherCon 2016: Francesc Campoy - Understanding nil

理解Go语言的nil

Is it a bug?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

|

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

type doError struct{}

func (e *doError) Error() string {

return ""

}

func do() error {

var err *doError

return err

}

func main() {

err := do()

fmt.Println(err == nil) // What's the result?

}

|

What’s the nil?

See a very, very, very familiar code.

1

2

3

|

if err != nil {

// do something....

}

|

Here is a summary about zero value of all types.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

bool -> false

numbers -> 0

string -> ""

pointers -> nil

slices -> nil

maps -> nil

channels -> nil

functions -> nil

interfaces -> nil

|

See an example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

type Person struct {

AgeYears int

Name string

Friends []Person

}

var p Person // Person{0, "", nil}

|

If a variable is only declared and has no assignment, it is zero value.

nil is a pre-defined variable, not a keyword.

1

2

|

type Type int

var nil Type

|

You can even change its value.

1

|

var nil = errors.New("hi")

|

But you should not do it.

What’s the usage of nil?

For Pointers

1

2

3

|

var p *int

p == nil // true

*p // panic: invalid memory address or nil pointer dereference

|

Dereference to nil pointer will cause panic.

What’s the usage of nil? Firstly see a code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

|

type tree struct {

v int

l *tree

r *tree

}

// first solution

func (t *tree) Sum() int {

sum := t.v

if t.l != nil {

sum += t.l.Sum()

}

if t.r != nil {

sum += t.r.Sum()

}

return sum

}

|

Two problems exist in this code. First is redundant code like:

1

2

3

|

if v != nil {

v.m()

}

|

Second is it will cause panic when t is nil.

1

2

|

var t *tree

sum := t.Sum() // panic: invalid memory address or nil pointer dereference

|

How to solve? Let’s see an example of receiver.

1

2

3

4

5

|

type person struct {}

func sayHi(p *person) { fmt.Println("hi") }

func (p *person) sayHi() { fmt.Println("hi") }

var p *person

p.sayHi() // hi

|

For pointer, even it is nil, the method of its object can be invoked.

So we can optimize the code like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

func(t *tree) Sum() int {

if t == nil {

return 0

}

return t.v + t.l.Sum() + t.r.Sum()

}

|

See more examples:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

|

func(t *tree) String() string {

if t == nil {

return ""

}

return fmt.Sprint(t.l, t.v, t.r)

}

// nil receiver are useful: Find

func (t *tree) Find(v int) bool {

if t == nil {

return false

}

return t.v == v || t.l.Find(v) || t.r.Find(v)

}

|

So if no special reason, avoid to use initialize function like NewX(). Just use the default value.

For Slices

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

// nil slices

var s []slice

len(s) // 0

cap(s) // 0

for range s // iterates zero times

s[i] // panic: index out of range

|

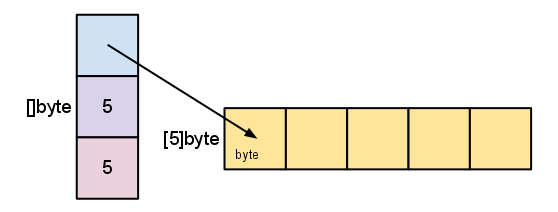

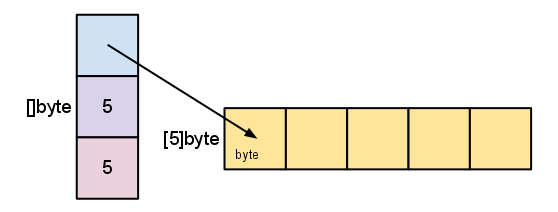

A nil slice can only not be indexed and all other operations can be done. Use append and it will be extended automatically. See slice data structure:

When there is an element in it, it will be like:

So no need to care about size of slice.

For Maps

Map, function and channel are special pointers in Golang and have their own implementation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

// nil maps

var m map[t]u

len(m) // 0

for range m // iterates zero times

v, ok := m[i] // zero(u), false

m[i] = x // panic: assignment to entry in nil map

|

nil map can be a readonly map.

What’s the usage of nil? See an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

|

func NewGet(url string, headers map[string]string) (*http.Request, error) {

req, err := http.NewRequest(http.MethodGet, url, nil)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

for k, v := range headers {

req.Header.Set(k, v)

}

return req, nil

}

|

When need to set header, we can:

1

2

3

|

NewGet("http://google.com", map[string]string{

"USER_AGENT": "golang/gopher",

},)

|

When no need to set header, we can:

1

|

NewGet("http://google.com", map[string]string{})

|

Or we use nil.

1

|

NewGet("http://google.com", nil)

|

For Channels

1

2

3

4

5

|

// nil channels

var c chan t

<- c // blocks forever

c <- x // blocks forever

close(c) // panic: close of nil channel

|

Close a nil channel will cause panic.

What’s the usage of nil channel? See an example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

func merge(out chan<- int, a, b <-chan int) {

for {

select {

case v := <-a:

out <- v

case v := <-b:

out <- v

}

}

}

|

If a or b is closed, <-a or <-b will return zero value without a stop. This is not expected. We want to stop merge value from a if it is closed. Change the code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

|

func merge(out chan<- int, a, b <-chan int) {

for a != nil || b != nil {

select {

case v, ok := <-a:

if !ok {

a = nil

fmt.Println("a is nil")

continue

}

out <- v

case v, ok := <-b:

if !ok {

b = nil

fmt.Println("b is nil")

continue

}

out <- v

}

}

fmt.Println("close out")

close(out)

}

|

When a or b is closed, set it as nil, it means the case will not be used because nil channel will be blocked forever.

For Interfaces

Interface is not a pointer, it contains two parts, type and value. Only when both of them are nil, it is nil. See:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

|

func do() error { // error(*doError, nil)

var err *doError

return err // nil of type *doError

}

func main() {

err := do()

fmt.Println(err == nil)

}

|

The output is false. Because the type of error is *doError and the value is nil, the error is not nil. So do not declare an error, just return nil.

1

2

3

|

func do() error {

return nil

}

|

See another code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

func do() *doError { // nil of type *doError

return nil

}

func wrapDo() error { // error (*doError, nil)

return do() // nil of type *doError

}

func main() {

err := wrapDo() // error (*doError, nil)

fmt.Println(err == nil) // false

}

|

The output is still false because although wrapDo returns error type, do returns *doError. So do not return typed error. Follow these 2 principles, then we can carefully use if x != nil.